“To walk through Djenné is to hear the earth remembering.”

In the heart of the West African Sahel—where the Niger and Bani rivers breathe life into a tapestry of floodplains—lies Djenné, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in sub-Saharan Africa. Its story stretches back over a thousand years, yet every sun-baked wall and winding alley seems to whisper the same truth: civilizations rise not only from power, but from the movement of ideas.

This deep-dive into Djenné opens The Griot’s Compendium, a series dedicated to lifting the veil on the peoples, places, and currents of global history often overshadowed in mainstream narratives.

I. Before the Empire: When Djenné Was Water and Song

Long before merchants arrived, before caravans stretched across the horizon, Djenné was a village of fishermen. The Bozo people, masters of the river, settled the region as early as 250 BCE. Their world revolved around the rhythms of water—the rising and falling of floods that nourished both soil and spirit.

In their stories, the river was not a boundary but a living ancestor.

It is said that the currents carried not only fish but messages, connecting communities along the waterways long before formal trade systems took root. This watery web of communication formed the earliest foundations of Djenné’s significance: a crossroads shaped by nature’s hand.

II. Djenné’s Rebirth: The Soninke and the Birth of a Trading Town (Early 13th Century)

By the early 1200s, a profound transformation had begun.

The Soninke people, heirs to the legacy of ancient Ghana (Wagadu), saw in Djenné something more than a fishing settlement. Positioned between the desert and the forest, the rivers and the caravan trails, the location was perfect for trade. The Soninke founded Djenné-Djeno, a new urban center built upon the wisdom of the Bozo lands yet designed for exchange at a global scale.

Here, the world converged:

- Salt caravans arrived from the Sahara, glittering like dunes turned to stone.

- Gold dust traveled from the southern forests, carried in calabashes.

- Cloth, beads, ivory, and kola nuts flowed through the city’s gates.

- And with these materials came something more precious: languages, philosophies, faiths, and technologies.

Djenné, by the 13th century, was more than a city.

It was an idea—the idea that Africa was never isolated, never passive, never forgotten, but fully engaged in the economic and intellectual conversations of the medieval world.

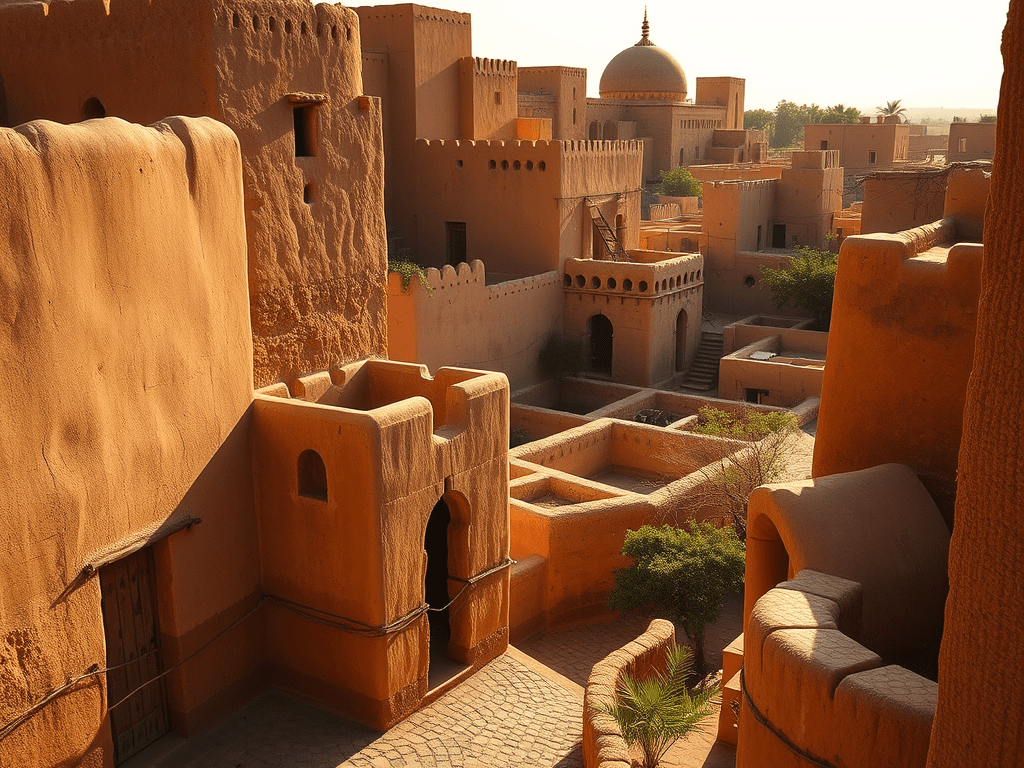

III. Earth and Spirit: The Architecture That Held a Civilization

Perhaps the most iconic symbol of Djenné is its architecture—especially the grand Djenné Great Mosque, later rebuilt in 1907 on earlier foundations. But even in the 13th century, the city was already famous for:

- Massive adobe structures shaped from mud, rice husks, and sun.

- Sudanese-Sahelian architecture, where walls curve like dunes and wooden beams jut outward like ribs of an ancient giant.

- Homes designed to stay cool under scorching heat, demonstrating engineering mastery rather than “primitive simplicity.”

These structures were not just homes; they were archives. The earth held memories of dynasties, droughts, festivals, and prayers whispered across centuries.

IV. A City of Scholars: Djenné and the Spread of Knowledge

By the late Middle Ages, Djenné was not only a marketplace but one of West Africa’s major intellectual centers, rivaling its sister city, Timbuktu.

Students traveled from across the region to study:

- Islamic jurisprudence

- Mathematics

- Astronomy

- Medicine

- Poetry

- History

Djenné became a place where learning flowed freely—where scholars debated ideas under the shade of mud-built towers and where libraries held manuscripts copied by generations of scribes with steady hands.

The city’s influence extended deep into the Mali Empire under Mansa Musa, whose pilgrimage in 1324 amplified West Africa’s reputation for wealth and scholarship.

V. The Pulse of Trade: Djenné at the Heart of a World System

Djenné played a crucial role in connecting three vast worlds:

- The Saharan world — salt, copper, textiles

- The Sahelian world — grains, livestock, leatherwork

- The forest world — gold, kola, spices, ivory

The city’s markets were layered and rich:

- Women traders bartered in bustling squares.

- Caravans unloaded travelers’ tales and goods.

- The rivers carried cargo to distant communities.

Djenné’s power did not come from armies but from movement—the movement of bodies, ideas, and wealth.

VI. Djenné Today: Memory in the Earth, Magic in the Air

Djenné remains a UNESCO World Heritage Site, its old town preserved like a living archive. Each year the community participates in the Crépissage, the ritual replastering of the mosque—a communal act that binds past and present.

The city stands as a reminder of a fundamental truth:

Africa’s medieval history is one of brilliance, innovation, architecture, global networks, and intellectual power.

Leave a comment